What happens when around 28 boxes from Site RF57 — a rescue excavation near Orpington from 1956-57 — find their way to the Museum of London? We decipher notes from lollipop sticks, find enough material for a potential movie script, and there is the unresolved case of the missing brooch!

The local museum at the 700-year-old Priory in Orpington had a relatively short but happy life. After a failed funding bid, the borough council was forced into a rethink and decided that a cost of £8 per visitor was too much to bear in difficult economic circumstances. The museum doors were closed. There was local opposition, but not enough to overturn the decision.

A dilemma was what to do with the archaeological material from several iconic sites which couldn’t be accommodated in the new Historic Collections display at the borough's Central Library. So, in 2016, 449 boxes found a new home at the Museum of London Archaeological Archive. It fascinated me from the day I started work at the museum around five years later, and I jumped at the chance to go through the material, unpack the stories and put them in order so that others could access this rich resource.

Site RF57: ‘earliest evidence of habitation’

So let me introduce you to Site RF57 — a rescue excavation near Orpington from 1956-57. In the years leading up to the redevelopment of the site into a school, there had been many prehistoric and Roman finds on the surface. Building a new school gave the council an opportunity to examine the archaeology and the Ministry of Works appointed a local assistant curator to oversee a group of volunteers in recovering what they could.

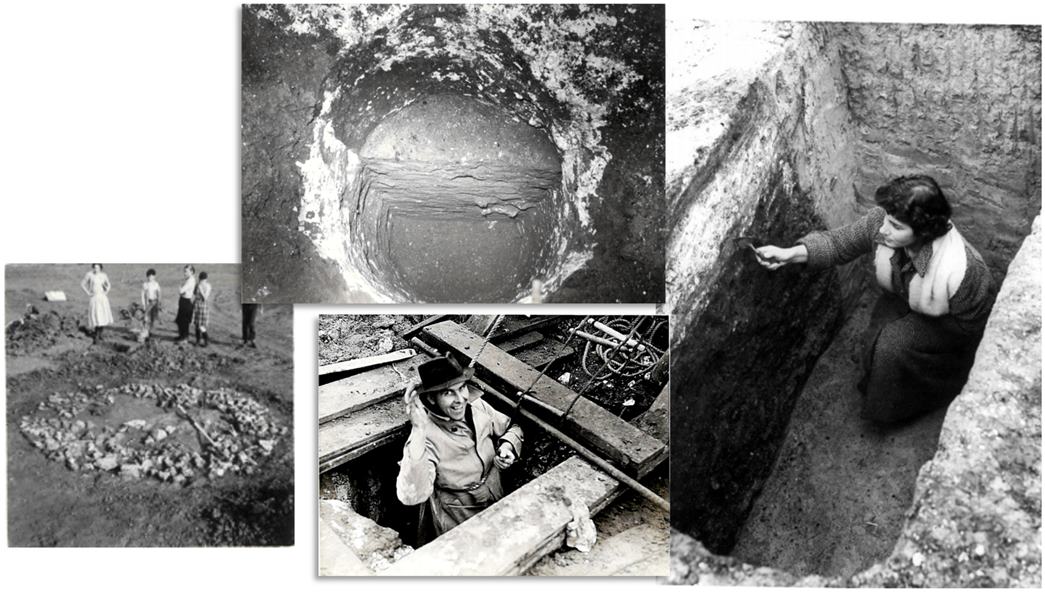

Archaeologist Dorothy Cox in The Book of Orpington (1983) says: “…remains of an Iron Age farmstead were found. These included corn drying kilns, postholes, storage pits, drainage ditches, a well over 55 feet deep, and pottery on the site dates the farmstead between c50BC – AD50. This is the earliest evidence of habitation …”

A tough row to hoe

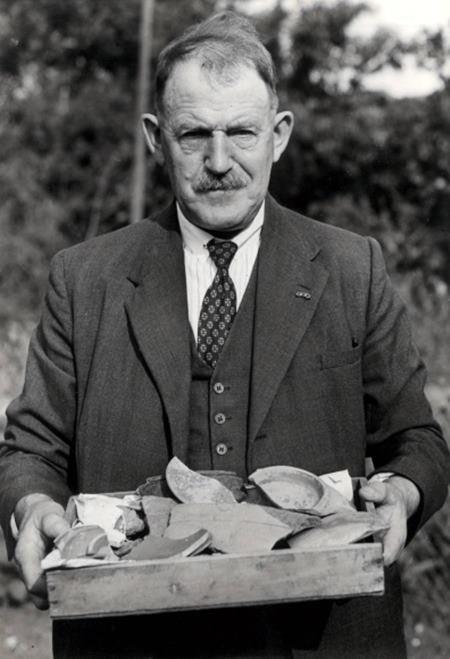

A Mr A. Eldridge with one of many trays of finds from the site. (©Museum of London)

Very early on I realised that it wasn’t going to be straightforward. Excavation and archiving was done very differently back in the day; and collection and recording 50 years ago was to very different — and sometimes bizarre — standards. Particularly if it was a rescue excavation!

Today, we use a technique called the Single Context Recording system, breaking each site down into the smallest possible units — called contexts — with each context representing a single event that happened in the past. For instance, a pit that has been filled twice over an extended time period, would have two contexts. Each of these events can be defined by looking at the differences in the soil — the colour, consistency, texture and what inclusions it may contain, and deciding that it is different to the context next to it.

Or, think of a trifle, where each layer is a context. So all finds from a single layer will be grouped together and given a unique number — such as RF57/1, /2, /3… — from a sequential register on site, and all finds from that deposit will then be associated with that context only.

Perhaps most importantly each context must be related to what is directly earlier and later than it. This chronological, or stratigraphic (layers from the bottom, i.e. earliest, to the top), relationship can be used to build a matrix — a visual framework that shows the relationship between all contexts in a trench and is the basis for understanding the history of any site.

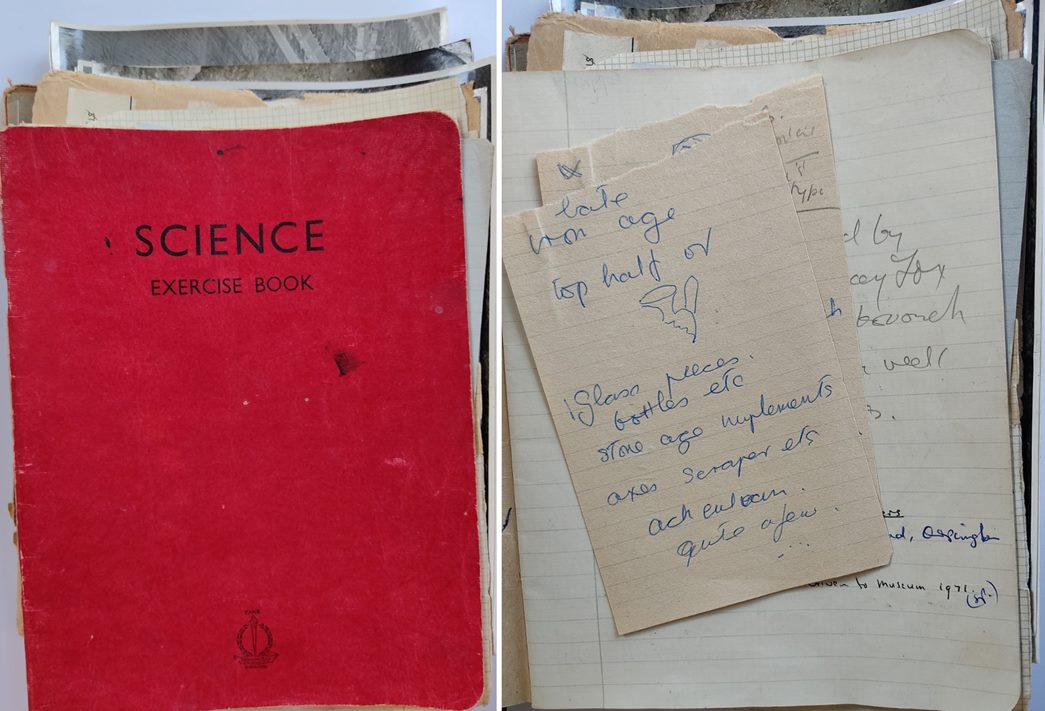

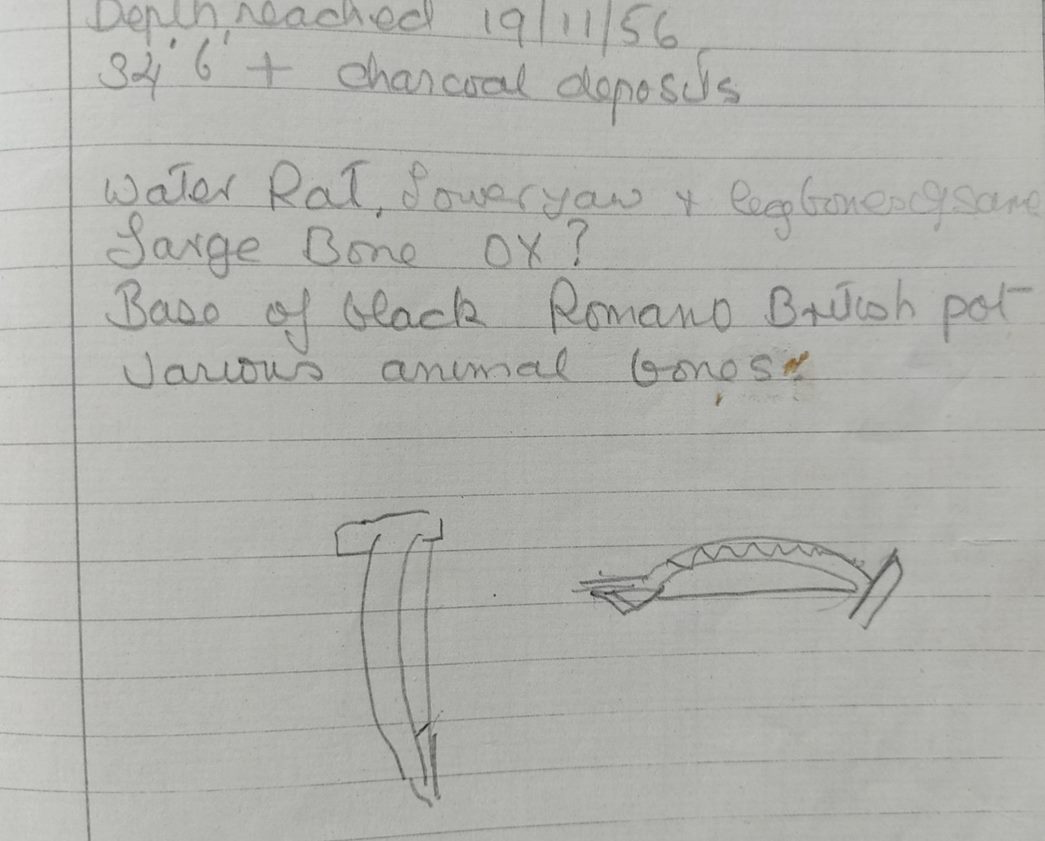

Opening the 28 boxes of finds and one small records box from this specific site, my heart sank. It seemed that most of the records were lost at some point and all that was left were some photographs, copies of correspondence and a worn notebook donated by one of the volunteers, Mrs Saunders, in 1971! In addition to this, there were no contexts, only named features that could no longer be located on a map. There had been little post-excavation work done, so some of the finds were in their raw state — unwashed and unsorted. And because everything was collected it included a lot of non-archaeological material such as unstruck flints and stones. We have a much more robust discard policy nowadays.

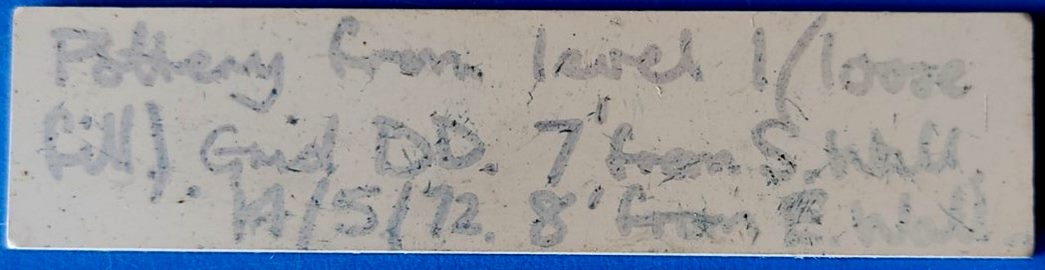

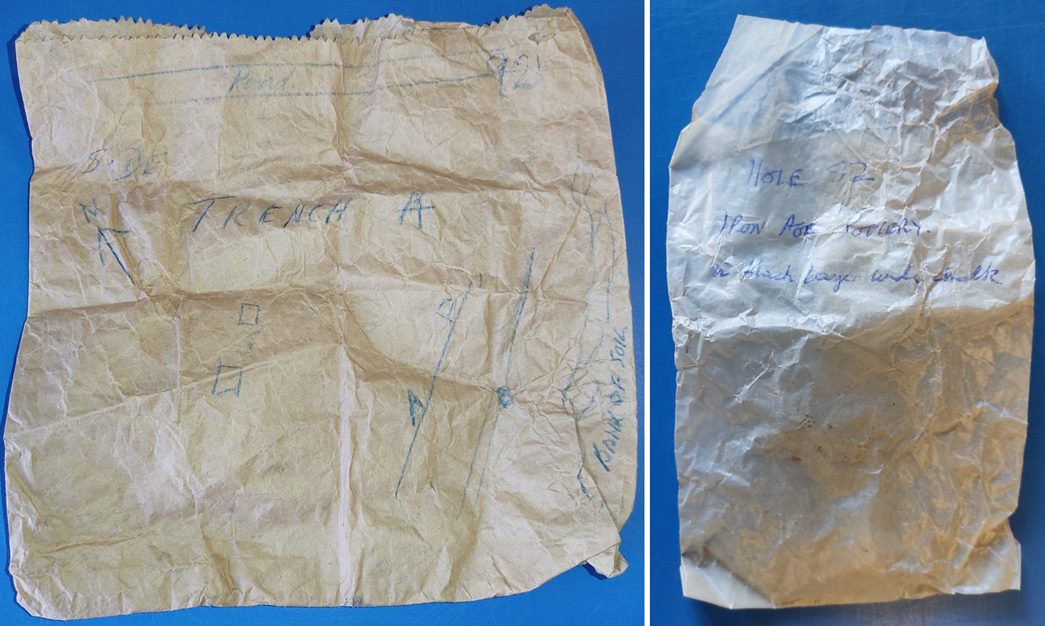

The bags of finds were marked with strange locations such as “pottery from level 1 (loose fill) Grid DD 7’ from S.W.wall…”, and there were notes and drawings on faded pieces of paper, paper bags and flat lollipop sticks!

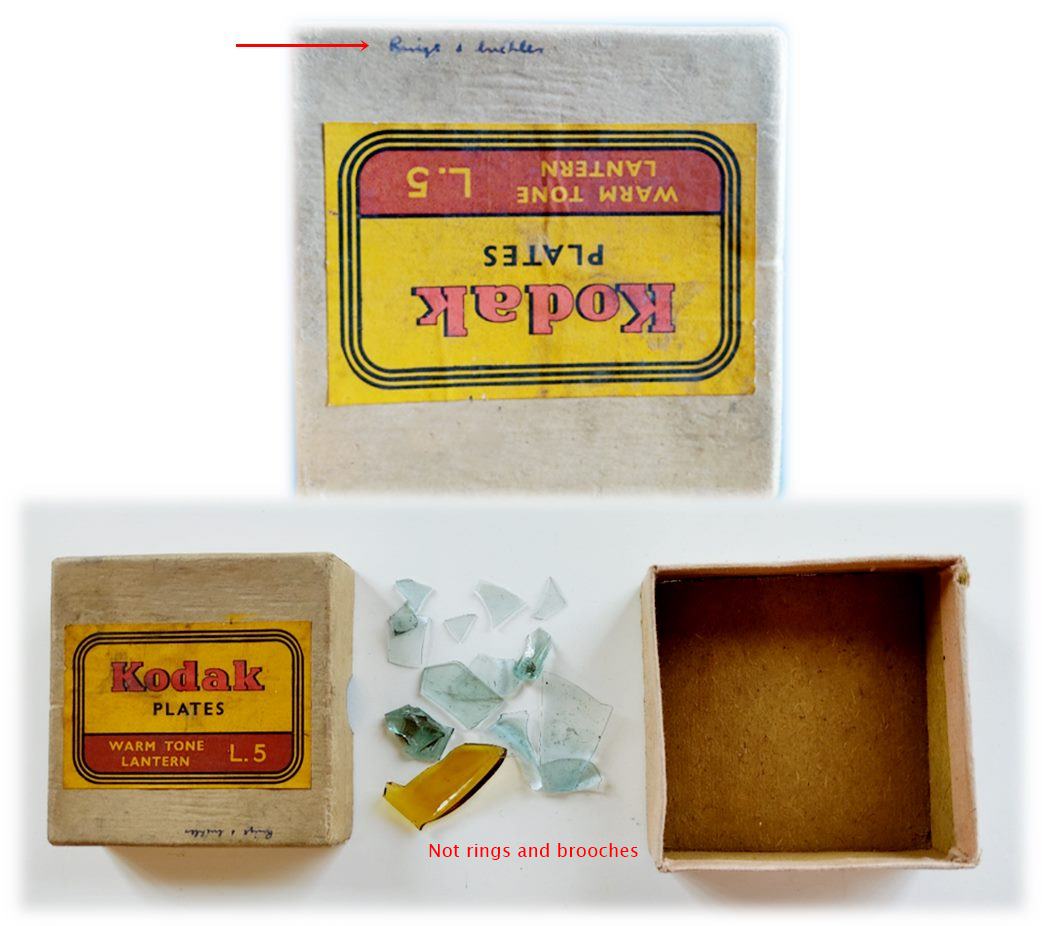

There were mysterious chocolate boxes, film boxes and aluminium cans for film rolls, which definitely didn’t contain what they said they did. A film box with “rings and brooches” written in small blue-ink lettering on its edge was opened with eager anticipation. Inside, were only small fragments of glass!

It seems that a brooch was indeed found in a deep well that was excavated by the owner of the notebook, and is referred to by others in the notes. However, this — as well as a finger ring — seem to have disappeared in the years since it was discovered.

The missing elements

The correspondence is interesting — revealing relationship breakdowns, resignations, distrust and obstruction. Someday this in itself would make a good film (The Dig 2?). It appears that a member of a local archaeological society was given some of the finds on the understanding that they would be taken to the museum, but they ended up in his personal possession until he was persuaded by the threat of legal action to give them up many years later. There isn’t a full list of finds or records, so it’s not known what they were or what happened to them? Fingers are firmly pointed at various participants. The last known sighting of the brooch seems to have been in 1965, but even that is uncertain.

While, in her book, Dorothy Cox, calls the site “the earliest evidence of habitation” — that’s not quite true. A group of Palaeolithic hand-axes found on the site (which are also part of the archive) are at least 200,000 years old. And the pottery pushes the date range well into the Roman period (50–410 AD). Frustratingly what could have been an important site with potential to examine the Iron Age to Roman transition now has limited potential.

The wins

There are positives to take from this, though. There are some significant finds from the site including an almost-complete Terra Nigra bowl with a potter’s stamp and several other potters’ stamps which could be investigated with a collection of pottery which can tell us something about the Iron Age / Roman London hinterland. And the well photographs, notes and finds can be compared to other similar sites, so we know that good work was done.

The material is now repacked and documented to current archival standards, in strong breathable bags labelled with the site code and some standard information on where we have it. The special finds are registered and recorded on software for better access and it will, henceforth, be stored in the best conditions for long-term preservation. This will ensure that present and future generations of researchers will be able to look at this piece of the jigsaw and use it to widen our understanding of the past.

My takeaways

From my own point of view, there are several things that come to life when you open the archive to this site — the thought of Mrs Saunders 55-ft down a well with her notebook, which she graciously donated. The local press photographer in his trench coat and trilby (this is true, there is a photograph of him!). Sadly the excavation director died in July 2020. It would have been lovely to speak to her and get the full story.

Not to forget my dream of tracking down that missing brooch! Some day!