The history of tea spans millennia. From its Chinese origins to ultimately becoming Britain's national drink, tea’s journey is entwined with colonial histories of sugar, porcelain and the East India Company’s global trade.

Although tea has come to be heavily associated with Britain as our national drink, its history spans across the globe and thousands of years. Here we dive a little deeper into the history of tea and what brews in the Museum of London’s collections.

First flush from China

This 'Chinaman' trade figure (1750–1800) was probably placed inside a store to indicate that tea from China was sold there. (ID no.: NN7327)

Tea originally came from China and was consumed there for thousands of years before Europeans became aware of the unique libation. In China, it had various meanings and purposes. Tea was used as a ceremonial drink and was also lauded as having medicinal properties.

The earliest account of tea drinking comes from China’s Shang dynasty (1500–1046 BCE), the first Chinese dynasty with archaeological evidence. This account attributes medicinal qualities to the drink. In the 16th century, it was Portuguese merchants and priests who became the first Europeans to encounter tea as they formed a nascent connection with China.

Tea and its importance were surprising to the Portuguese at first, as recorded in Empire of Tea, but by the 1620s, Europeans in China were already consuming the drink as part of their everyday diet and even sending small amounts abroad.

Tea first arrived in Britain in the 1650s via the Dutch East India Company, which was also bringing tea to places like Paris and Holland. Amounts were small and tea was expensive – 60 shillings (about £300 now) per pound for the best quality, which was 10 times the price of the best coffee. Many who could afford tea kept it locked away as it was so prized, says Sainsbury Archive Archivist Allison Foster.

Tea was served in London’s already popular coffee houses and largely consumed by elites. However, by the end of the 17th century, tea was still somewhat of a mystery in Britain, particularly for the majority of the population who still did not have access to the beverage, but also to those elites who were trying to understand it.

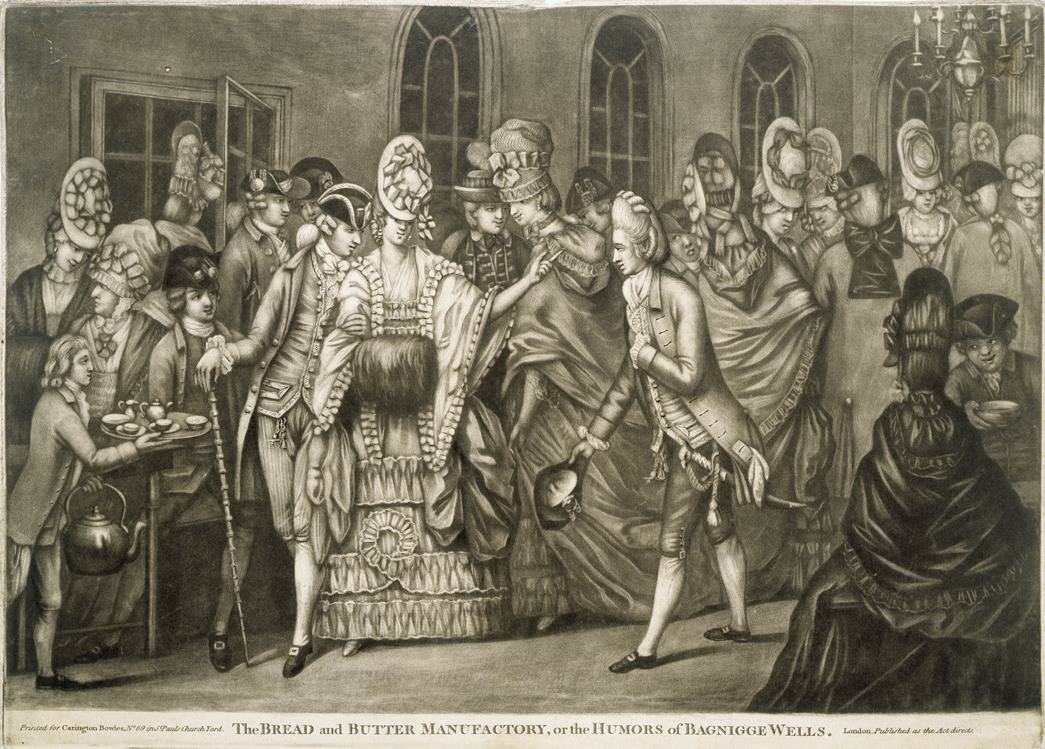

The Bread and Butter Manufactory

Groups of tea drinkers are shown in the Long Room at Bagnigge Wells House, a popular place of entertainment for Londoners. (ID no.: A6928)

Tea began to arrive in Britain in significant amounts from the beginning of the 18th century. Over 200,000 pounds of tea was imported during 1700–1704 via large ships called East Indiamen. As imports increased, tea also became more available to the middle classes. However, even as its popularity grew there was still a lot of debate about the meaning of this foreign beverage and how it was becoming more entrenched in British life. Detractors argued that it was an example of wasteful luxury with no nutritional value and a tendency to encourage gossip and immorality.

Brewing popularity of tea

There was a large increase in tea consumption in Britain across the 18th century. It became a regular grocery item and tea trade cards soon became a collectible. Alongside the growth in popularity of tea was an increase in sugar consumption by four times. Sugar being produced on Caribbean plantations using the labour of enslaved African people was being used to sweeten tea in Britain. Tea ceremonies at home became popular and alongside tea’s rise came an increasing desire for Chinese porcelain. In 1734, the East India Company imported over a million items of Chinese porcelain.

Porcelain tea bowls, 18th century

Tea bowls such as the one imported from China (left) and those made in England but with Chinese designs were popular among tea drinkers. (ID nos.: 57.51/170a; 74.3/10)

British manufacturers also began to make porcelain. For instance, a porcelain tea bowl in the museum’s collection dates from the mid-18th century and was created at The Bow factory established in the 1740s. Bow porcelain became extremely popular among the upper and middle classes, and the factory was known as ‘New Canton’ as it was modelled after a factory in Canton, China. The blue and white colours and patterns showing flowers and rivers mimic the Chinese porcelain that was so sought after. The Museum of London has many porcelain items in its collections that were created to mimic Chinese porcelain products and more can be found via a search in our online collections.

High taxes meant that tea smuggling was a very successful and profitable business with more tea being smuggled into Britain than imported legally to satisfy the appetite of people of all classes who now loved tea. This was until Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger reduced the tea tax in 1784 resulting in the end of mass tea smuggling. As tea became more ever-present in Britain it took a starring role in shops. By 1785, there were 30,000 wholesalers and retailers in Britain registered as tea merchants.

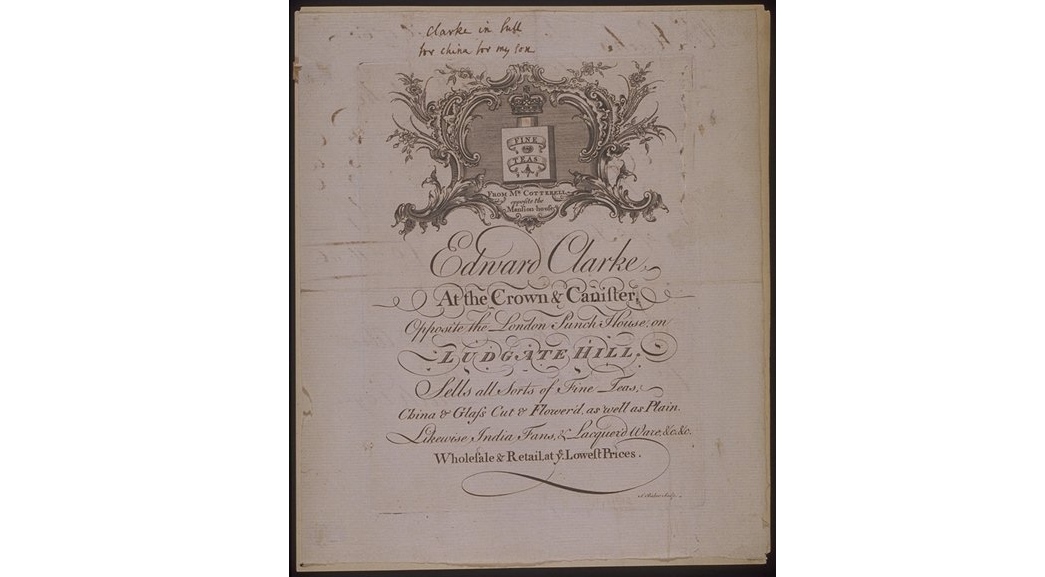

Tea merchant trade receipt, 1760

Copper-engraved trade receipt publicising the business of Edward Clarke tea merchant and supplier of India fans, and more. (ID no.: Z1704/187)

This receipt from 1760 shows how tea was often advertised. It’s for “Edward Clarke tea merchant and supplier of India fans, lacquerware and china and glass”, and includes the trade sign that would have hung outside the shop to identify it as a place selling tea at the Crown and Canister opposite the London punch house on Ludgate Hill. The card has a tea canister surmounted by a crown, enclosed within a decorative cartouche. A handwritten invoice on the back with the date “April 17th 1760” refers to the supply of coffee cups, tongs, basins and other household goods to a Mrs Hucks.

A nation of tea drinkers

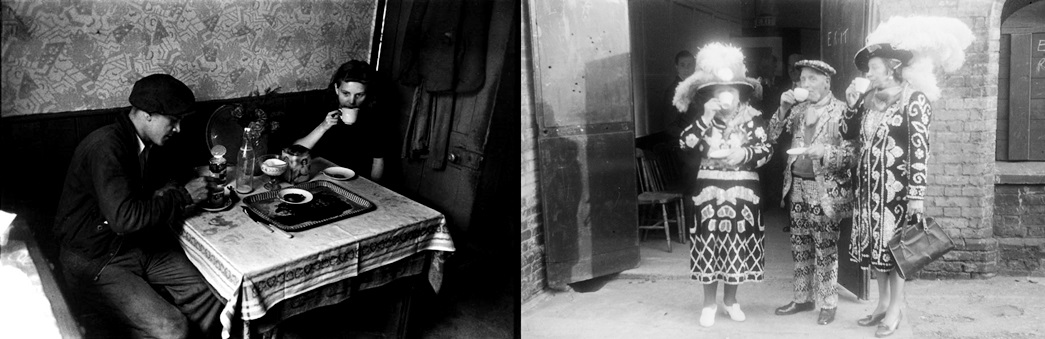

From the 1820s onwards, almost everyone in Britain was drinking tea. Be it at home like this couple in Whitechapel or as break during festivities like the Pearly King and Queens. (ID nos: IN7287, Courtesy The Humphrey Spender Archive; HG1328/20, ©Henry Grant Collection)

Britain as a ‘land of tea drinkers’

By the 1820s, Britain had a strong identity as being a “tea-drinking nation”. The global tea industry evolved further in the mid-19th century when tea began to be produced in what was British India. From the mid-1850s, tea from India began to arrive and within 35 years it surpassed tea from China. In the 20th century, a number of the innovations we associate with our tea nowadays developed. Brands selling consistent black tea were born, including recognisable names like Lipton, Lyons and Typhoo (which owned and managed large tea plantations in India, Sri Lanka and Africa). Tea bags were invented in the US and Tetley became the first brand to use them in the UK in 1953.

Tea and the empire

(left) Teacup and saucer commemorating the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria, 1897; and the Empire tea centenary celebrations that took part in London in 1939. (ID nos: 38.192/3; IN25069)

Conflicting associations with tea

Nowadays, tea is considered the national drink of Britain. But it’s also important to remember the difficult journey. From trade politics to being grown across the empire in large plantations run by the British, and flavoured using sugar produced in the Caribbean by enslaved and indentured people – tea can evoke a myriad of emotions, particularly when considered alongside the intertwined histories of empire and the sugar trade.

Our current Museum of London Docklands display Holding Emotions examines the difficult emotions that objects from our London, Sugar, and Slavery gallery can evoke, including a Worcester Tea Cup (1751–1760). The display was created alongside the mental health charity MIND, which worked with young people from the youth organisation Taking Shape Association to explore wellness tools and responses to difficult histories, including that of tea.

Holding Emotions is a free display offering a moment to reflect on, process and release emotions at the London, Sugar, and Slavery gallery at the Museum of London Docklands, 10am–5pm.

Header image: The ‘refreshment department’ of the Women's Exhibition, May 1909. This two-week fundraising and recruitment event organised by the Women's Social and Political Union. (ID no.: IN1291)

Love history and trivia? Subscribe to our

free History of London newsletter for stories from our collections,

displays and exhibitions.