Uncover the enduring allure of the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage, tracing its medieval roots through London’s fascinating collection of scallop shell tokens, symbols of an age-old journey that still captivates modern travellers.

In the Museum of London’s collection of over 1,000 pilgrim souvenirs, at least 34 include the iconography of scallop shells. Spread across different saints and pilgrimages, including that of Canterbury and its patron saint Thomas Becket, this shared symbol was not as common, and it piqued our interest. Attempting to trace the origins of the ‘pilgrim’s shell’, we found that they were once symbolic of a very specific pilgrim’s route.

Of the 34, around 15 medieval tokens – including badges, pendants and ampulla (tiny containers) – can be linked to the Spanish pilgrimage site Santiago de Compostela. It was the third most important pilgrimage destination after Jerusalem and Rome. It was believed that the body of the apostle St James, who was martyred in AD 42, had been miraculously transported from Jerusalem to Galicia, Spain. By the 11th century, his shrine at Compostela was attracting pilgrims from all over Europe. Many Londoners undertook the long and dangerous journey there, visiting a string of European shrines on the way.

St James’ symbol

(left) A portrait print with engraving representing St James of Spain; and (right) a pilgrim badge from the shrine of St James in Santiago de Compostela in north-west Spain.

These tokens are emblematic of that spiritual expedition and how London has always been connected to different parts of the world. In 1434 alone, roughly 2,310 pilgrims were licensed to sail to Spain from English ports. When William Wey of Eton College made the journey home from Compostela in 1456, he noted the diversity of the pilgrims at the Spanish port: “They included English, Welsh, Irish, Normans, Bretons, and others”.

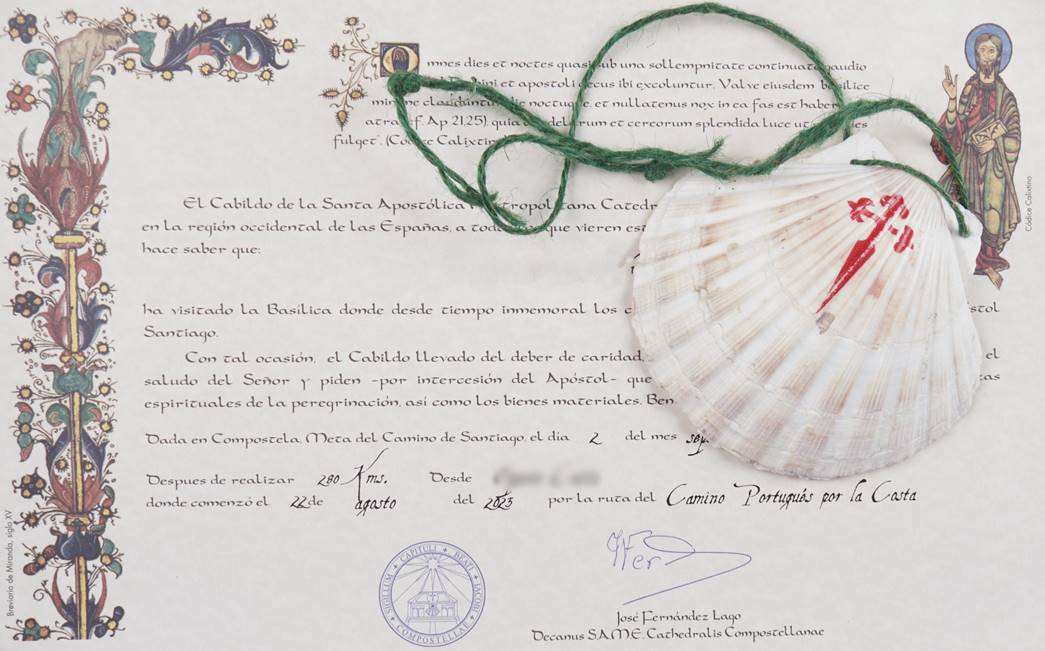

The pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, known as the Camino de Santiago (Way of St James), remains a cherished and meaningful journey for modern-day Britons. Over 10,000 people from England alone undertook the pilgrimage in 2023.

There are several modern certified pilgrim routes from England and further afield across Europe to Compostela shrine. This includes the Camino Francés from France, the Camino Portugués from Portugal, and the Camino Inglés from England. Today, to earn your certificate of completion from Santiago de Compostela’s cathedral, you need to walk (or cycle) at least 100km from start to finish.

Remitting sins and the Santiago de Compostela

Historically, medieval pilgrims would travel to such sites as a devotional practice, seeking absolution or favour from God, or for saintly protection. In his account, William Wey explains, “Whoever has come on pilgrimage to the church of St James, son of Zebedee, at any time, has one-third of all his sins remitted.”

This practice was underpinned by the medieval belief in the power of holy relics and their shrines as a direct connection to God. However, as can be seen in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, pilgrimages also provide the opportunity for social gathering – mingling religious devotion with tourism.

Today, many modern pilgrims are motivated by similar reasons. For instance, in 2023, statistics from the cathedral indicate that 42.65% of pilgrims participated for solely religious reasons. While 22.79% had no devotional motivation, demonstrating how others see the pilgrimage as a cultural experience or even as a fitness adventure. You need only to look through the Confraternity of St James (CSJ) bulletins to better understand the many reasons people go on the camino. In August 2000, 15-year-old William Riddington Young, his brother and father walked to raise money for their new local branch of St John’s Ambulance. For William Morrison-Bell in July 2016, his journey was initially to celebrate his retirement, but through walking, he said, “For the first time, I feel free, in a sort of ecstasy.”

While the souvenirs we have are from the Middle Ages, modern-day pilgrims are also presented with a scallop shell when they complete the journey. But what’s the connection of the scallop with such pilgrimages?

Scallops as a symbol of divine protection

Originally emblematic of St James and Santiago de Compostela, from the 11th century onwards, the scallop shell gradually transformed into a universal symbol for pilgrims. It was appropriated for a range of different pilgrimage sites, most prominently Thomas Becket, as pilgrim tokens. Pilgrims would wear them around their necks or pin them onto clothes or bags.

Native to the Galician region of Spain, the significance of the scallop shell goes beyond just an association with St James. In the medieval period, pilgrims used scallop shells as utensils to scoop their portions of food and water at the food kitchens dotted along the routes. Its symbolic significance is multifaceted. Just as the shell protects a creature in the sea, on pilgrimage, it represents divine protection. Further, as it became associated with a physical journey, scallop shells were connected with personal transformation, and emotional and spiritual growth.

When actual scallop shells proved to be in short supply in the medieval period, enterprising badge makers stepped in, fashioning metal versions to cater to the growing demand. These artificial souvenirs spanned a wide range of materials. Affordable metal badges, particularly lead alloy, were popular among pilgrims, and the earliest examples in London date to the late 13th century. Some of these badges would even be cast with the figure of St James on them.

How the Spanish jet came to London

For the discerning travellers who could afford them, carved jet tokens were a more luxurious alternative to the lead badges. Jet was a local resource of north-western Spain so ‘azabacheros’ (speciality jet carvers) capitalised on the increased demand created by the many pilgrims, creating their own guild. Through these pilgrims, Spanish jet made its way to London like a meticulously crafted and exquisite jet and silver-gilt pendant in the museum’s collection.

More than just a souvenir, the badges became a physical focus for the devotion of medieval pilgrims, and could act like a protective religious amulet. For those who wanted an extra special souvenir from their travels, possibly for their paying benefactor, pilgrims might acquire ampulla filled with holy water or oil. The design of the scallop shell was also used for these medieval containers. With ampulla, medieval pilgrims could return home with blessed oil from Santiago de Compostela, and use the holy liquid to consecrate their family members, home, shop or fields. These medieval scallop shell souvenirs from Santiago de Compostela can be found across Britain, from central London to the islands of Scotland. Ultimately, these tokens allowed pilgrims to maintain a tangible connection to their journey – acting as a devotional tool as well as a memento.

Today, Londoners continue to bring back these symbolic shells as tokens of their pilgrimage, breathing new life into this medieval tradition and bridging the gap between the past and the present.

For more information on the Santiago de Compostela and the Camino Inglés, you can contact the Confraternity of St James.

Love history and trivia? Subscribe to our free History of London newsletter for stories from our collections, displays and exhibitions.